Carretera Austral Part 3: Caleta Gonzalo - La Junta

Originally posted to El Cantar de la Lluvia on Monday, March 05, 2007

The ferry's loading ramp was raised, and we slowly pulled away from Hornopirén. The bikes were tucked away in a corner, normally unused space that we were lucky to be able to occupy. The sea was calm.

The weather was nice, though on deck, the wind cooled anything that was not sheltered. Witness the only use that Camilo's cap got during the entire trip.

And so it goes: we had to spend the night. Caleta Gonzalo is within the controversial Parque Pumalín. The first thing you notice upon arrival are the occasional constructions and structures: information center, cafeteria, and so on. Built from wood, well-finished, they give the impression that they were carefully designed and built to simulate an ethno gift and decoration shop. Or perhaps something out of Jurassic Park. It just looked as if they were trying too hard, but that's just me.

We were informed that there are two camp sites. One is 500 metres away and costs 1500 pesos per person. The other, quite some distance away, is more expensive. Or should we just gas it to Chaitén? No, better camp. So off we shuffle with the other semi-dazed travellers.

Off to the side of the road was a small and narrow car parking space; beyond, a short stone wall, and above it, overgrown shrubs and trees. And then a break in the stone wall, and a gaping black hole in the vegetation, dark and spooky as anything you've ever seen. A couple of cyclists wheeled their bikes past us and disappeared in the hole. Since screaming and munching sounds did not ensue, we decided we'd brave it, and started unpacking. We had noticed a DR650 by the entrance, and we did what every biker would: went over and looked at its kit. The rack looked like a cooked noodle, and it had some sort of horrendous rack/frame for panniers made with steel construction bars (yes, the type you normally pour concrete over) rusted and apparently once painted with spray paint. Despite these details, the bike sported a Kryptonite U-lock and a Xena disc lock plus alarm. An interesting contradiction.

The way in was narrow. Did I mention it was dark? Night had fallen as we unpacked the bikes. The trail ran sometimes along the forest floor, sometimes on nice quaint elevated walkways. And soon, 30 cm from the ground and spaced every few metres, those nice dim path lights that some people use on their front lawns. This was not like camp sites I know.

Further ahead, a human traffic jam. Cyclists and backpackers were clogging the narrow path, and two guys in jackets and caps were charging a fee before people crossed the long hanging bridge.

We paid, crossed the bridge, straining under the weight of *all* our luggage (so as not to leave anything unattended on the bikes), and on the other side... a surprise. It looked like a garden from someone's large house in the very well-off corner of Santiago: Stone paths, neatly trimmed grass, islands of bushes and plants here and there, no doubt laid out according to the teachings of Feng Shui, and the aforementioned garden lights. By the entrance after coming out of the forest were large information panels made from hand-carved wood, ethno lettering and so on. They informed the visitor about the private nature of the park and similar things.

We set up the tents and headed off towards the common cooking area, some quinchos with picnic tables. Camilo had managed to find the only guy wearing a touring jacket, and the three of us sat down to eat crappy food and chat. It turns out that Nicolás had worked at ING while Camilo was there. He told us about his bike's rack, how it had had a more dignified start in life, at least during the conceptual stage. He had even tried having it made by Alejandro Muñoz, the same guy that made my rack and who was, by now, quite well known amongst Santiago bikers.Unfortunately Alejandro said he wouldn't be able to make it in a few days, so Nicolás set off to Lira, the motorcycle street, to find the first guy with a welding kit that could throw it together. If I'm not mistaken he took it to Lifan, importers of the ever crappy, ever failing chinese bikes that are flooding the Chilean market. He had no need to continue, for I knew already where the source of its crappiness lay. They did a half-assed job, and by 7 pm, when they closed shop, it was still not ready. He took it home as it was, and the paint was a last-ditch attempt at keeping rust at bay. Nico was now on his way home (he'd reached Caleta Tortel), and it had broken several times since he set out.

That night I discovered the loss of my sleeping mat. It was very cold. I had to use my sheepskin seat liner to insulate myself from the ground. It was so cold, I took a few swigs from the pisco hip flask I had. And I think I lit the gas stove in the tent.

The next morning, sun!

Chaitén was close, so we wouldn't stop there.

Glaciers!

If I'm not mistaken, this is Puente Yelcho, inaugurated towards the end of the 90s. Before that you needed a barge to get across.

Yelcho Glacier.

Villa Santa Lucía.

I came around a curve, and there was Camilo chatting with another biker. And that's how we met Tom Paprocki, from Wisconsin (www.themanifestdestiny.org). He had come all the way from home on his KLR, nicknamed El Jugoso.

Doubltess my favourite sticker is the "Chofer Mimoso" one. Usually seen in urban buses and taxis in Latin America, it roughly translates as "Cuddly Driver".

He was going at a slower pace than we were not only because he was alone, but more importantly because he was involved in a serious accident in Bolivia, fault of a truck driver, that sent his riding buddy back to a US hospital.

I love these road signs. Surely they were out of uphill signs, and rotated a downhill sign.

We noticed that our home made bash plate was also a cowshit plate. Is that the biggest skid mark you've seen or what?

In La Junta we took a cabin for the three of us, made pasta, and befriended Tom.

There is an amazingly well stocked supermarket at La Junta. They have everything. This is also the only point where you can use a debit/credit card for hundreds of kilometres in any direction. As if that weren't enough, they are also a Copec gas station. The supermarket also has a few internet points, a bizarrely advanced point-of-sale system running on a couple of recent PCs at the counter, several surveillance cams, fresh fruit, cheese, everything. And outside, speakers playing music, apparently a looped CD of La Oreja de Van Gogh. Check it out on Youtube to get a feel for what we were being exposed to.

Something interesting from the Vialidad.cl website:

That was La Junta in 1981, with 40 houses. And today:

I recommend you take a look at the Vialidad website (if you speak spanish); they've put together a wonderful photographic essay of the different parts of the Carretera Austral, all packed with interesting info.

A few parting words on speedboats. Think of the speedboats you've seen throughout your life: Don't most of them lie forgotten in garages and patios? To me, they are sculptures that remind us that not all purchases made by the Man of the family are wise, or well considered. But anyway. Perhaps some day this boat will see water again.

Next Chapter: La Junta - Puerto Aysén

| Days 5 and 6: Ferry from Hornopirén to Caleta Gonzalo, La Junta. |  |

The ferry's loading ramp was raised, and we slowly pulled away from Hornopirén. The bikes were tucked away in a corner, normally unused space that we were lucky to be able to occupy. The sea was calm.

The weather was nice, though on deck, the wind cooled anything that was not sheltered. Witness the only use that Camilo's cap got during the entire trip.

Deep and monotonous humming from the ferry's engines. I am on the highest deck, sitting near the hot air grille leading down to the engine room. It's not that cold, and my jacket is warm. An hour ago we left Caleta Ayacara behind, a place where the ferry stops once a week on Thursdays. No sign of the toninas, the local dolphins that usually keep ships company in their crossing of these traits and fjords.

Some chat, some sleep. We are about thirty people, perhaps more, if you count those that are stil sitting in their vehicles. Ah, and one sheep, of course. It was brought aboard at Caleta Ayacara by pushing and pulling, and it peed in protest.

I am surprised at the amount of houses south of Caleta Ayacara. Kilometres and kilometres of shoreline, and a house or two every 100, 200 metres. Every now and then, a church. Behind, the tree-covered hills, and beyond, clouds and a sky that was at times blue, at times white.

Another ventilation duct, now at the stern, middle level. The sun is thirty minutes away from setting. I feel the heat of the sun, the hot air, and the reflection of the sun on the water. I have been all over the ship, looking for the sheep, and I can't find it anywhere. Do they have a sheep locker?

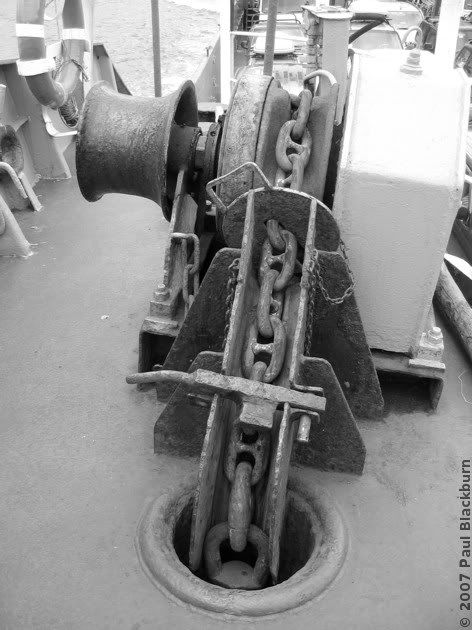

Rust, and the thick marine paint that resists it. Objects and contraptions so massive that rust, should it appear, is not a preoccupation. Anyway. Siting across from me, a heavy metal fan, in a hooded top, Morbid Angel's logo on the chest. He lazily plays an imaginary drum kit formed by his thighs, his knees and his feet. The hot air, permanent rumbling of the engines and the sound of the churning water, the fizz after it comes up all frothy and white, all of that is making me sleepy.

We will get to Caleta Gonzalo late; spending the night is no longer an option.

And so it goes: we had to spend the night. Caleta Gonzalo is within the controversial Parque Pumalín. The first thing you notice upon arrival are the occasional constructions and structures: information center, cafeteria, and so on. Built from wood, well-finished, they give the impression that they were carefully designed and built to simulate an ethno gift and decoration shop. Or perhaps something out of Jurassic Park. It just looked as if they were trying too hard, but that's just me.

We were informed that there are two camp sites. One is 500 metres away and costs 1500 pesos per person. The other, quite some distance away, is more expensive. Or should we just gas it to Chaitén? No, better camp. So off we shuffle with the other semi-dazed travellers.

Off to the side of the road was a small and narrow car parking space; beyond, a short stone wall, and above it, overgrown shrubs and trees. And then a break in the stone wall, and a gaping black hole in the vegetation, dark and spooky as anything you've ever seen. A couple of cyclists wheeled their bikes past us and disappeared in the hole. Since screaming and munching sounds did not ensue, we decided we'd brave it, and started unpacking. We had noticed a DR650 by the entrance, and we did what every biker would: went over and looked at its kit. The rack looked like a cooked noodle, and it had some sort of horrendous rack/frame for panniers made with steel construction bars (yes, the type you normally pour concrete over) rusted and apparently once painted with spray paint. Despite these details, the bike sported a Kryptonite U-lock and a Xena disc lock plus alarm. An interesting contradiction.

The way in was narrow. Did I mention it was dark? Night had fallen as we unpacked the bikes. The trail ran sometimes along the forest floor, sometimes on nice quaint elevated walkways. And soon, 30 cm from the ground and spaced every few metres, those nice dim path lights that some people use on their front lawns. This was not like camp sites I know.

Further ahead, a human traffic jam. Cyclists and backpackers were clogging the narrow path, and two guys in jackets and caps were charging a fee before people crossed the long hanging bridge.

We paid, crossed the bridge, straining under the weight of *all* our luggage (so as not to leave anything unattended on the bikes), and on the other side... a surprise. It looked like a garden from someone's large house in the very well-off corner of Santiago: Stone paths, neatly trimmed grass, islands of bushes and plants here and there, no doubt laid out according to the teachings of Feng Shui, and the aforementioned garden lights. By the entrance after coming out of the forest were large information panels made from hand-carved wood, ethno lettering and so on. They informed the visitor about the private nature of the park and similar things.

We set up the tents and headed off towards the common cooking area, some quinchos with picnic tables. Camilo had managed to find the only guy wearing a touring jacket, and the three of us sat down to eat crappy food and chat. It turns out that Nicolás had worked at ING while Camilo was there. He told us about his bike's rack, how it had had a more dignified start in life, at least during the conceptual stage. He had even tried having it made by Alejandro Muñoz, the same guy that made my rack and who was, by now, quite well known amongst Santiago bikers.Unfortunately Alejandro said he wouldn't be able to make it in a few days, so Nicolás set off to Lira, the motorcycle street, to find the first guy with a welding kit that could throw it together. If I'm not mistaken he took it to Lifan, importers of the ever crappy, ever failing chinese bikes that are flooding the Chilean market. He had no need to continue, for I knew already where the source of its crappiness lay. They did a half-assed job, and by 7 pm, when they closed shop, it was still not ready. He took it home as it was, and the paint was a last-ditch attempt at keeping rust at bay. Nico was now on his way home (he'd reached Caleta Tortel), and it had broken several times since he set out.

That night I discovered the loss of my sleeping mat. It was very cold. I had to use my sheepskin seat liner to insulate myself from the ground. It was so cold, I took a few swigs from the pisco hip flask I had. And I think I lit the gas stove in the tent.

The next morning, sun!

Chaitén was close, so we wouldn't stop there.

Glaciers!

If I'm not mistaken, this is Puente Yelcho, inaugurated towards the end of the 90s. Before that you needed a barge to get across.

Yelcho Glacier.

Villa Santa Lucía.

I came around a curve, and there was Camilo chatting with another biker. And that's how we met Tom Paprocki, from Wisconsin (www.themanifestdestiny.org). He had come all the way from home on his KLR, nicknamed El Jugoso.

Doubltess my favourite sticker is the "Chofer Mimoso" one. Usually seen in urban buses and taxis in Latin America, it roughly translates as "Cuddly Driver".

He was going at a slower pace than we were not only because he was alone, but more importantly because he was involved in a serious accident in Bolivia, fault of a truck driver, that sent his riding buddy back to a US hospital.

I love these road signs. Surely they were out of uphill signs, and rotated a downhill sign.

We noticed that our home made bash plate was also a cowshit plate. Is that the biggest skid mark you've seen or what?

In La Junta we took a cabin for the three of us, made pasta, and befriended Tom.

There is an amazingly well stocked supermarket at La Junta. They have everything. This is also the only point where you can use a debit/credit card for hundreds of kilometres in any direction. As if that weren't enough, they are also a Copec gas station. The supermarket also has a few internet points, a bizarrely advanced point-of-sale system running on a couple of recent PCs at the counter, several surveillance cams, fresh fruit, cheese, everything. And outside, speakers playing music, apparently a looped CD of La Oreja de Van Gogh. Check it out on Youtube to get a feel for what we were being exposed to.

Something interesting from the Vialidad.cl website:

That was La Junta in 1981, with 40 houses. And today:

A few parting words on speedboats. Think of the speedboats you've seen throughout your life: Don't most of them lie forgotten in garages and patios? To me, they are sculptures that remind us that not all purchases made by the Man of the family are wise, or well considered. But anyway. Perhaps some day this boat will see water again.

Next Chapter: La Junta - Puerto Aysén

Labels: carreteraaustral, rides, trips

The Lagoons of the Santuario de la Naturaleza 2: Laguna Los Ángeles

The Lagoons of the Santuario de la Naturaleza 2: Laguna Los Ángeles Race Day At Leyda 4

Race Day At Leyda 4 El Tabo and the Central Hidroeléctrica El Sauce

El Tabo and the Central Hidroeléctrica El Sauce Exploring The Hills Around Lampa

Exploring The Hills Around Lampa A Different Route To Baños De Colina

A Different Route To Baños De Colina The Mines of the Cuesta La Dormida

The Mines of the Cuesta La Dormida The Frozen Lagoons of the Santuario de la Naturaleza

The Frozen Lagoons of the Santuario de la Naturaleza Second Mass Demonstration "For A Fair Tag"

Second Mass Demonstration "For A Fair Tag" First Mass Demonstration Against The 'Tag'

First Mass Demonstration Against The 'Tag' Enduro In Lagunillas

Enduro In Lagunillas Embalse El Yeso and Termas Del Plomo

Embalse El Yeso and Termas Del Plomo Ride To Peñuelas

Ride To Peñuelas Cerro Chena

Cerro Chena Race Day at Leyda 3

Race Day at Leyda 3 Baños de Colina 2

Baños de Colina 2 Carretera Austral: Epilogue

Carretera Austral: Epilogue The Little Giant and Termas del Plomo

The Little Giant and Termas del Plomo Back on Two Wheels

Back on Two Wheels 2006 Photographic Retrospective

2006 Photographic Retrospective Race Day At Leyda 2

Race Day At Leyda 2  Quantum Optics III in Pucón

Quantum Optics III in Pucón Meseta In Chicureo

Meseta In Chicureo Pick Up Your Beer Bottle And Fuck Off

Pick Up Your Beer Bottle And Fuck Off  Planes And Hills

Planes And Hills Cut-Off Road

Cut-Off Road Lagunillas

Lagunillas Laguna Verde 2

Laguna Verde 2 Ride To Anywhere But Aculeo

Ride To Anywhere But Aculeo Cerro El Roble, Second Attempt

Cerro El Roble, Second Attempt Baños De Colina

Baños De Colina Some Walk On Water...

Some Walk On Water... Race Day At Leyda

Race Day At Leyda Almost Cerro El Roble

Almost Cerro El Roble Off To Curacaví with Andrés

Off To Curacaví with Andrés La Serena, Part 3: Back To Santiago

La Serena, Part 3: Back To Santiago  A Bull, Two Cows and a Chilean Fox

A Bull, Two Cows and a Chilean Fox Escape To Cuesta La Dormida

Escape To Cuesta La Dormida Valve Adjustment

Valve Adjustment La Serena, Part 2B: Valle Del Elqui

La Serena, Part 2B: Valle Del Elqui La Serena, Part 2A: Coquimbo and La Recova

La Serena, Part 2A: Coquimbo and La Recova Mud And Pine Trees

Mud And Pine Trees La Serena, Part 1

La Serena, Part 1 Pimp My Exhaust

Pimp My Exhaust Ride To Laguna Verde

Ride To Laguna Verde Ride To La Mina

Ride To La Mina Ride To Termas El Plomo

Ride To Termas El Plomo Camping in Colliguay

Camping in Colliguay Ride To Portillo

Ride To Portillo Ride To Olmué and Con Con

Ride To Olmué and Con Con Siete Tazas

Siete Tazas Watching The Departure Of The Day That Brought Me Here

Watching The Departure Of The Day That Brought Me Here Buenos Aires Motorbikes

Buenos Aires Motorbikes Ride to Talca with the Adach Group

Ride to Talca with the Adach Group Las Trancas '05

Las Trancas '05 Towers and Hills

Towers and Hills María Pinto, Melipilla, Aculeo

María Pinto, Melipilla, Aculeo Me and my Carb

Me and my Carb